Abraham van Diepenbeeck: The Golden Rays of Christ

- Dec 7, 2023

- 3 min read

Updated: Dec 28, 2024

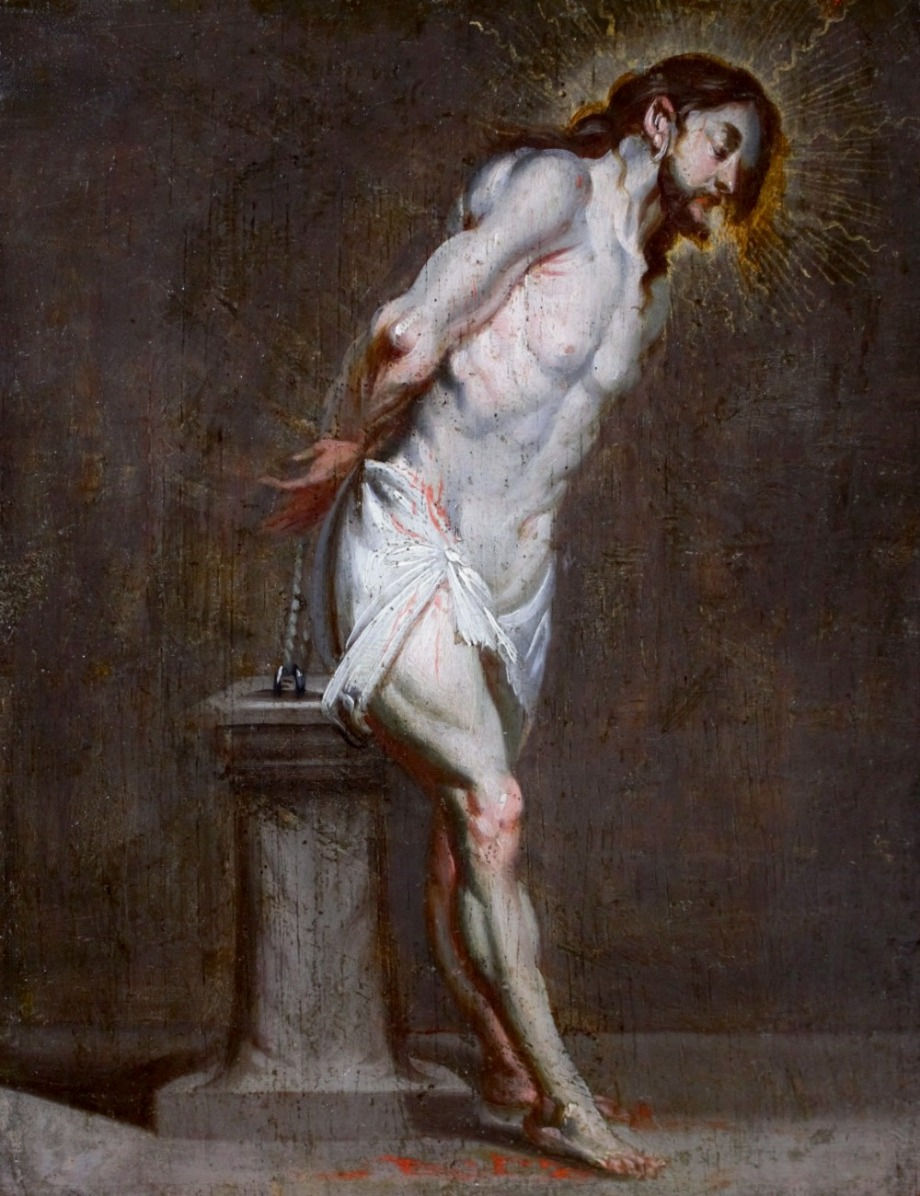

During the weekend of May 6th, I navigated through the enthusiastic crowd at Trafalgar Square, the plaza in front of the National Gallery in London. Despite the pouring rain and the scent of beer in the air, many Britons were convincingly adorned in the national colors of blue, white, and red, complete with cheerful flags. Unlike the others, my purpose was not to catch a glimpse of the new royal couple, Charles III and Camilla, but to acquire a painting. The artwork in question was a panel titled Christ Bound to a Column, attributed to the flemish Old Master painter Abraham van Diepenbeeck (1596-1675).

As an art dealer specializing in the period from 1850 to 1950, my usual focus differs, but a particular fascination for 17th-century paintings led me to this acquisition. Works from this era often lack signatures, including this one where the selling party, an auction house, couldn't fully guarantee Van Diepenbeeck's authorship. However, the high quality of the piece prompted me to delve deeper into the life of this accomplished artist.

Christ with a Golden Ray Crown

Abraham van Diepenbeeck, a prominent Flemish painter active in Antwerp, received his education under Peter Paul Rubens. Born in 's-Hertogenbosch, he showcased his versatility as a history painter, glass painter, and designer for tapestries and prints. While influenced by his mentor, Van Diepenbeeck often employed stronger light-dark contrasts in depicting mythological and religious subjects. A notable member of the Antwerp Saint Luke's Guild, he also served as the court painter for Archbishop Leopold Wilhelm of Austria.

The panel depicts Christ in a subdued manner, clad only in a loincloth, leaning forward with closed eyes. The painting is based on a New Testament passage: 'Then Pilate took Jesus and scourged Him' (John 19:1, Matthew 27:24, Mark 15:15). The blood spatters on his pallid skin and the puddle of blood on the ground reveal recent scourging. Van Diepenbeeck left out the scourgers, focusing solely on Christ's suffering, rendering the work exceptionally devotional and contemplative.

Remarkable is the halo, crafted with "shell gold." This technique involves a meticulous process of mixing very fine gold particles with Arabic gum, applied with a brush. The name originates from the medieval practice of using shells to hold valuable pigments. The precious "shell gold" was seldom used, reserved for details and accents, and Van Diepenbeeck learned this technique in Rubens' studio.

Charles Blanc's Connection

On the return journey in the Eurostar, with the painting securely stored in a special case, my research continued. The back of the panel features a 19th-century handwritten label attributing the work to Van Diepenbeeck in French. The name Blanc is also noted. Charles Blanc (1813-1882) was a respected professor and art critic, best known for his series, "Histoire des peintres de toutes les écoles." In volume 10, "École Flamande" from 1864, he discusses Abraham van Diepenbeeck, illustrating his biography with five reproductions. One of these reproductions depicts Christ at a column, the same image as the London panel. While dimensions and materials are unspecified, there's a possibility that it's the same artwork; the piece certainly has an artistic connection to the work in Blanc's book. This discovery adds value, as the auction house overlooked this 19th-century literary reference.

A painting related to this panel is a life-size canvas by Van Diepenbeeck in the collection of the Museum Catharijneconvent in Utrecht, The Flagellation of Christ. Christ is depicted in a similar, mirrored pose, with the scourgers visible. The composition draws inspiration from a print by Lucas Vorsterman (1595-1675), based on a painting by Gerard Seghers (1591-1651). Could the London panel be an elaborated oil sketch for the painting in the Museum Catharijneconvent? Why is the composition mirrored? Did Van Diepenbeeck create the panel as a study, directly from Seghers' original? Unfortunately, Charles Blanc does not provide these answers.

Now, several months later, the restored painting adorns the wall—a memento of a truly "royal" weekend.